Understanding the Transactional Nature of Smart Contracts

In this post I attempt to summarize my understandings about the transactional nature of Smart contract execution. I conducted this study, while trying to understand the DAO exploit. The basis of the DAO exploit is a recursive(or rather reentrant) message call. One important point to note that an exception(during a message call or otherwise) in the Ethereum Virtual Machine , would imply reverting all changes to state and balance. Solidity has a documentation on cases where exceptions are thrown automatically. However in certain cases like send we need to manually raise an exception using throw. So, the attacker has to be careful not to hit any exceptions while attempting the reentrant call to avoid reverting. I also rectify certain mistaken assumptions, I made in my previous post.

So let us start by looking at the simplified version of a reentrant bug, as mentioned in multiple blogs and the paper Making Smart Contracts Smarter.

1 contract SendBalance {

2 mapping (address => uint) userBalances;

3 bool withdrawn = false;

4 function getBalance(address u) constant returns(uint){

5 return userBalances[u];

6 }

7 function addToBalance() {

8 userBalances[msg.sender] += msg.value;

9 }

10 function withdrawBalance (){

11 if (!(msg.sender.call.value(

12 userBalances[msg.sender])())) { throw; }

13 userBalances[msg.sender] = 0;

14 }}

The code above clearly demonstrates a coding anti pattern in line 11 and 13 where the receiver is sent the amount in line 11 and his balance is zeroed out later, whereas clearly we should have coded it the other way around. However, please do note this is not the DAO contract. This is a much simpler contract and had the DAO contract been written this way, the sent amount would have been reverted, if the call.value ran into an exception. I will expand upon this statement in a bit.

One of my principal sources of confusion was the rollback mechanism of the EVM and whether rolling back would result in reverting the balance to the sender. And is sending money equivalent to a side effect?

Well, an expression or a function is a side effect if it modifies some state outside its scope or has an observable interaction with the outside world. In this case if we take a look at the operational semantics of the EVM in the Ethereum yellowpaper:

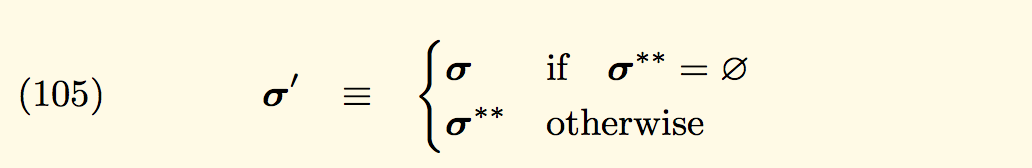

As we can see above, whenever an exception occurs the world state σ should be reverted to the point prior to intermediate state σ’. Now the question is what is σ? And does it capture the account balance within its scope? Well of course. According to the yellowpaper, σ is used to denote the World State, which is a mapping between addresses and account states. Implementations of the paper, models this mapping as a Merkle Patricia Trie. And being an immutable structure it allows any previous state (whose root hash is known) to be recalled by simply altering the root hash accordingly.

So rolling back would simply involve altering the root hash of the Merkle Patricia trie. Hence if an Account A owns 50$ and Account B owns 100$. And while attempting to send 5$ from Account A to Account B an exception is thrown(manually using throw), the root hash of the trie would be reverted to the one where A and B owns 50$ and 100$ respectively. Interested readers can look at the model of the State, in the C++ implementation of Ethereum here.

Now, let us confirm the same fact from the documentation of Solidity, which states:

The effect of an exception is that the currently executing call

is stopped and reverted (i.e. all changes to the state and balances

are undone) and the exception is also “bubbled up” through Solidity

function calls (exceptions are send and the low-level functions call,

delegatecall and callcode, those return false in case of an exception).

The above is pretty self explanatory. Let us verify the above with a Contract of our own. There is a lot of documentation out there about setting up an ethereum client and running a full node or a test node. I preferred to use geth for my experiments. Also for simplification of the process of deploying your contracts and playing around with them, you can use testrpc. Testrpc comes with 10 test accounts. For deployment and contract development in general I would suggest people to use the Truffle framework which does the compilation, linking, deployment and binary management. Also for contract programmers from India, Kraken and Coinbase does not trade ethers in India currently. You can purchase ethers from Ethex India. I will be using a very simple token contract as mentioned in the examples of geth with slight modifications:

pragma solidity ^0.4.9;

contract token {

mapping (address => uint) public coinBalanceOf;

/* Initializes contract with initial supply tokens to the creator of the contract */

function token(uint supply) {

coinBalanceOf[msg.sender] = supply;

}

/* Very simple trade function */

function sendCoin(address receiver, uint amount) returns(bool sufficient) {

if (coinBalanceOf[msg.sender] < amount) return false;

coinBalanceOf[msg.sender] -= amount;

coinBalanceOf[receiver] += amount;

if (!receiver.send(amount))

throw;

return true;

}

}

The geth tutorial covers everything about setting up your account. The modification which I have made is removing the event CoinTransfer and instead sending the coin using send and actually checking if an exception occurs during the send, in that case I explicitly throw. This is an additional statement to be executed before deploying the contract:

personal.unlockAccount(web3.eth.accounts[0], "<Your password here>")

Upon compiling the contract, the solc online compiler will give you the gas estimates. In this case:

Creation: 20341 + 122600

External:

coinBalanceOf(address): 353

sendCoin(address,uint256): unknown

So let us load our account with less gas so that the sendCoin can fail and an exception be thrown. With the basic initialization in place and following the documentation, when we call the sendCoin function, we encounter an exception. If we were to inspect the state of eth.accounts[1](the receiver) it still wouldn’t have any token and the entire supply would reside with eth.accounts[0](the sender), which implies a proper rollback takes place. Please do note that if you go ahead with this, the gas will end up being consumed.

So, having done this experiment, if we return to look at the code, I mentioned at the beginning of my post, the vulnerable function looks like this:

1 function withdrawBalance (){

2 if (!(msg.sender.call.value(

3 userBalances[msg.sender])())) { throw; }

4 userBalances[msg.sender] = 0;

5 }}

If this was indeed the DAO contract, the moment call.value would return false, throw would be called which raises an exception and the entire transaction would be reverted to its old state. Also it is a bad idea to use call.value in place of send. Because send, by default, doesn’t forward any gas to the receiver. However call.value does that and would allow the receiver to make reentrant calls without burning any gas for the message call in between. Please note, if I had not manually checked for the send to return a false, no exception would occur and the balance would end up getting transferred, despite of running out of gas. We can conduct an experiment on the same by deploying the Token contract using the CoinTransfer event as mentioned in the geth docs. The key takeaway for a contract developer is this:

- The concept of rollback is tied to an exception. Exceptions result in rollback.

- The

sendfunction of Solidity returnsfalseon facing an exception. You have to manually check and use athrowstatement to trigger the rollback.

For those interested to study the DAO contract in detail it can be found over here: The original DAO contract. Phil Daian and Peter Vessenes have done a very good job of explaining the DAO attack line by line in their respective blogs. I would urge the interested reader to head there to understand the DAO exploit in depth, which deserves a separate post on its own. The only thing I would like to point out is the most vulnerable part in that contract:

1 // Burn DAO Tokens

2 Transfer(msg.sender, 0, balances[msg.sender]);

3 withdrawRewardFor(msg.sender); // be nice, and get his rewards

4 totalSupply -= balances[msg.sender];

5 balances[msg.sender] = 0;

6 paidOut[msg.sender] = 0;

7 return true;

Of course the anti-pattern of ‘sending the amount first and zeroing out later’ is visible in line 3 onwards. Another critical bug as pointed by Peter Vessenes is in line 2, where the Transfer function is called instead of transfer(Note the capitalization). The transfer function would reduce the user balance before the vulnerable withdraw, hence the call should have looked more like

if (!transfer(0 , balances[msg.sender])) { throw; }

instead of

Transfer(msg.sender, 0, balances[msg.sender]);

PART 2 : INTERNALS OF THE ROLLBACK MECHANISM

[Note: The following sections might not be of much utility if you are looking for advice on writing contracts. They principally document my excursions into the EVM codebase and might contain some incorrect or incomplete information, as I have just started researching and understanding the Ethereum codebase.]

We have inferred from Part 1 of this blog post that the throw statement in Solidity is a very useful construct for triggering rollbacks. So in all those scenarios where exceptions are not raised automatically, we can use throw to conveniently rollback. So what exactly happens when you throw in Solidity?

We can find it in the Contract Compiler

bool ContractCompiler::visit(Throw const& _throw)

{

CompilerContext::LocationSetter locationSetter(m_context, _throw);

// Do not send back an error detail.

m_context << u256(0) << u256(0);

m_context << Instruction::REVERT;

return false;

}

So what exactly is this Instruction::REVERT? Lets look at the Instruction source

/// Virtual machine bytecode instruction.

enum class Instruction: uint8_t

{

\..\

REVERT = 0xfd, ///< halt execution, revert state and return output data

INVALID = 0xfe, ///< invalid instruction for expressing runtime errors (e.g., division-by-zero)

SELFDESTRUCT = 0xff ///< halt execution and register account for later deletion

};

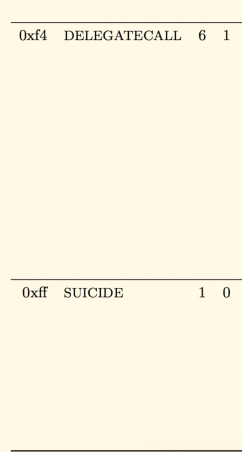

So we find something interesting here, REVERT corresponds to 0xfd in the EVM bytecode but also next to it we find an instruction called INVALID which signals runtime errors like division by zero. Together 0xfd and 0xfe corresponds to the handling of Runtime exceptions in the EVM. Together these 2 constitute the bread and butter of the rollback mechanism in EVM. So let us open the Ethereum yellow paper and find these corresponding instructions in the instruction set:

Well this is awkward! The EVM instruction set does not specify 0xfd and 0xfe. So we can have a general intuition that EVM would tend to rollback in case it encounters an instruction which is not defined in its Instruction Set. Let us verify that. I tried verifying this in both the ethereumj - the Java implementation of the EVM as well as cpp-ethereum - the C++ implementation of the EVM. Lets start.

ETHEREUMJ

[Note: Feel free to skip to the section on cpp-ethereum because I was not successful in tracing the entire rollback flow in ethereumj :( ]

Looking at the Opcode source file in Java, sure enough we cannot find any definition of the 0xfe or 0xfd instruction. Now if we look at the source code of the VM we find this:

try {

BlockchainConfig blockchainConfig = program.getBlockchainConfig();

OpCode op = OpCode.code(program.getCurrentOp());

if (op == null) {

throw Program.Exception.invalidOpCode(program.getCurrentOp());

}

\..\

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

logger.warn("VM halted: [{}]", e);

program.spendAllGas();

program.resetFutureRefund();

program.stop();

throw e;

} finally {

program.fullTrace();

}

We see that on encountering an invalid opcode, it throws a runtime exception(To study all the exceptions look here). Followed by that, on encountering that exception its spends all the gas, resets all future refunds and then finally builds the full trace and throws the exception. Now I am very sure someone who is catching this final throw e is most probably doing the rollback. But I wasn’t able to trace back the entire flow. I am still working on it. I had better luck with the C++ implementation below.

CPP-ETHEREUM

Similarly like Java we cannot find the 0xfe and 0xfd instruction defined in the C++ instruction source. So let us see what the code does when it encounters this invalid opcode:

void VM::interpretCases()

{

INIT_CASES

DO_CASES

{

\...\

DEFAULT

throwBadInstruction();

}

WHILE_CASES

}

It calls throwBadInstruction(). This function wraps it in boost::exception and throws a runtime exception which is caught here:

\..\

catch (VMException const& _e)

{

clog(StateSafeExceptions) << "Safe VM Exception. " << diagnostic_information(_e);

m_gas = 0;

m_excepted = toTransactionException(_e);

revert();

}

It sets the gas to 0 and calls revert(). The revert() looks interesting:

void Executive::revert()

{

if (m_ext)

m_ext->sub.clear();

// Set result address to the null one.

m_newAddress = {};

m_s.rollback(m_savepoint);

}

We have finally hit gold. The revert() function is rolling back the mutable state to a previous save point. Lets look inside:

void State::rollback(size_t _savepoint)

{

while (_savepoint != m_changeLog.size())

{

auto& change = m_changeLog.back();

auto& account = m_cache[change.address];

// Public State API cannot be used here because it will add another

// change log entry.

switch (change.kind)

{

case Change::Storage:

account.setStorage(change.key, change.value);

break;

case Change::Balance:

account.addBalance(0 - change.value);

break;

case Change::Nonce:

account.setNonce(account.nonce() - 1);

break;

case Change::Create:

m_cache.erase(change.address);

break;

case Change::NewCode:

account.resetCode();

break;

case Change::Touch:

account.untouch();

m_unchangedCacheEntries.emplace_back(change.address);

break;

}

m_changeLog.pop_back();

}

}

We have finally arrived at the State file, which is the facade for operating on the Merkle Patricia Trie. A point of interest is the m_changeLog here which looks like this

std::vector<detail::Change> m_changeLog;

It is similar to the Transaction Log structure that I mentioned in my previous blog post. Any atomic change to any account is registered and appended in the changelog. In case some changes must be reverted, the changes are popped from the changelog and undone. The kinds of changes are pretty self explanatory.

Balancesignifies change in Account balance.Storagesignifies Account storage modification.Noncesignifies Nonce being increased by 1.Createsignifies Account creation.NewCodesignifies new code being added to an accountTouchsignifies touching an account for the first time.

All these are logged as atomic state change entries. The changelog is managed with the rollback(), savepoint() and commit() methods. [C++ note to self: auto& means when you want to work with original items and may modify them.]

Through this exercise we could understand the rollback mechanism of the EVM. For future work I will be looking more deeply into the Ethereum yellowpaper and try and understand the various other workflows inside the EVM.